字幕と単語

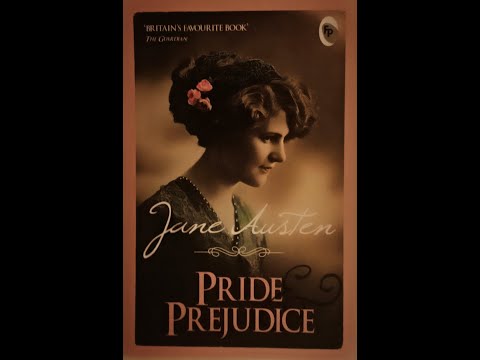

Pride & Prejudice | Chapter 1-5 (Audiobook)(Pride & Prejudice | Chapter 1-5 (Audiobook))

00

林宜悉 が 2023 年 10 月 12 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

general

US /ˈdʒɛnərəl/

・

UK /'dʒenrəl/

- adj.一般的な;大まかな;広範囲に適用できる;総司令官の

- n. (c.)大将

- n. (c./u.)一般大衆;一般的な研究分野

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除