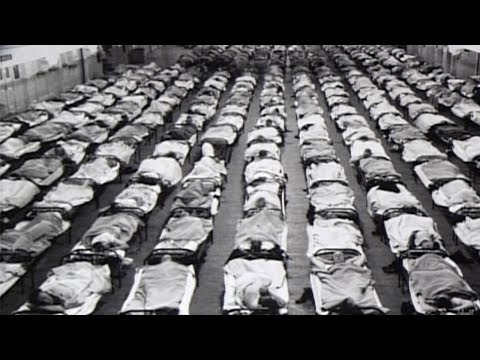

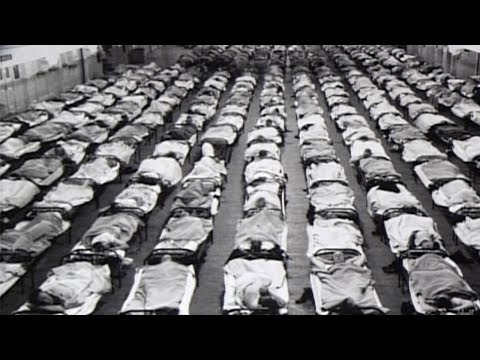

第1章|1918年インフルエンザ (Chapter 1 | Influenza 1918)

林宜悉 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /ɪˈlɪməˌnet/

・

UK /ɪ'lɪmɪneɪt/

US /ˈmɪzərəbəl, ˈmɪzrə-/

・

UK /ˈmɪzrəbl/

- n. (c./u.)病気;植物病;弊害

- v.t.むしばむ

US /rɪˈlɛntlɪs/

・

UK /rɪ'lentləs/

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除