字幕と単語

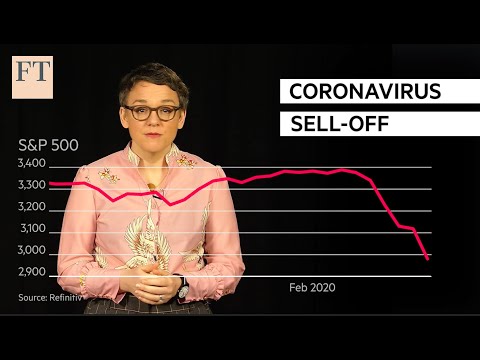

コロナウイルス:市場はいかにして脅威に目覚めたか|FT (Coronavirus: how markets woke up to the threat | FT)

00

林宜悉 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

tough

US /tʌf/

・

UK /tʌf/

- adj.噛みにくい;骨の折れる : つらい : きつい;厳しい;(物が)丈夫な : 頑丈な;強い;話しづらい;暴力的な

- n.タフな人

- v.t.鍛える

- v.t./i.耐え抜く

A2 初級

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除