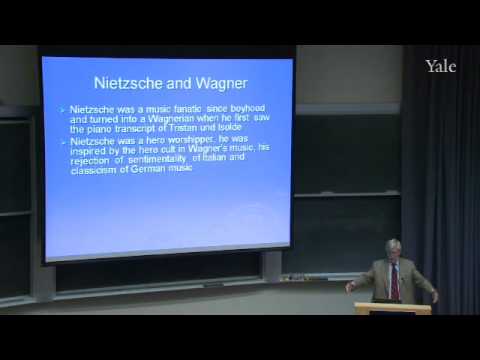

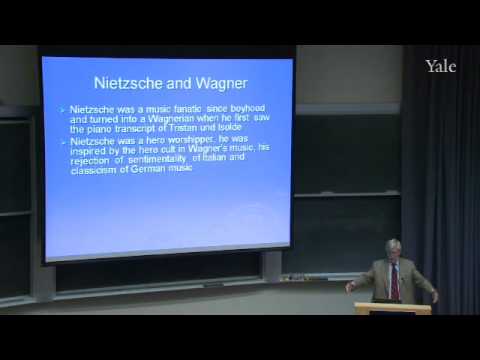

14.力・知識・道徳についてのニーチェ (14. Nietzsche on Power, Knowledge and Morality)

黃崇竣 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /ˈʌltəmɪt/

・

UK /ˈʌltɪmət/

- adj.根本的な;偉大な;最終的な;最大の

- n.アルティメット;極み;最終

US /ˈkrɪtɪkəl/

・

UK /ˈkrɪtɪkl/

- adj.批判的な;重大な;批評の;批判的な;重篤な

US /rɪˈleʃənˌʃɪp/

・

UK /rɪˈleɪʃnʃɪp/

- n. (c./u.)関係;関わり;恋愛;親族;業務;数学

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除