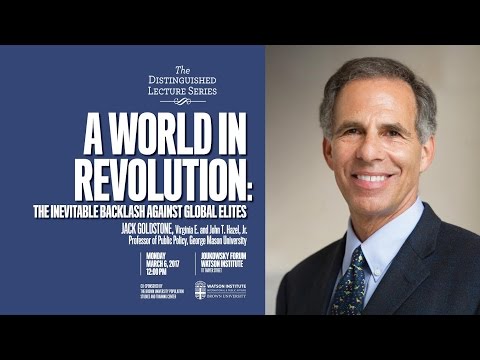

革命の中の世界グローバルエリートへの必然的な反発 (A World in Revolution: The Inevitable Backlash against Global Elites)

王惟惟 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありません- n. (c./u.)条件;期間;学期;用語;関係;項;妊娠期間;任期

- v.t.称する

US /ædˈvæntɪdʒ/

・

UK /əd'vɑ:ntɪdʒ/

- n. (c./u.)有利な点;強み : 長所;利益

- v.t.利用する

US /fɔrs, fors/

・

UK /fɔ:s/

- n.軍隊;力;強制;武力;影響力;勢い;警察

- v.t.強要する;こじ開ける;促成栽培する

- n. (c./u.)気持ち;分別ある判断力;意味

- v.t./i.(感覚器官で)感知する : 気づく;感じる

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除