字幕と単語

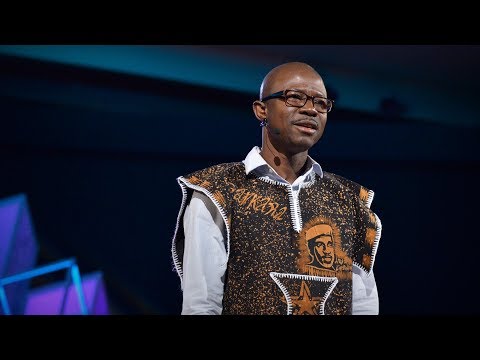

TED】草加モーゼス。エボラの生存者のために、危機は終わっていない(エボラの生存者のために、危機は終わっていない|草加モーゼス (【TED】Soka Moses: For survivors of Ebola, the crisis isn't over (For survivors of Ebola, the crisis isn't over | Soka Moses))

00

Zenn が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

experience

US /ɪkˈspɪriəns/

・

UK /ɪk'spɪərɪəns/

- n. (c.)経験;経験;経験;体験

- n. (c./u.)経験;職務経験

- v.t./i.経験する

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除