字幕と単語

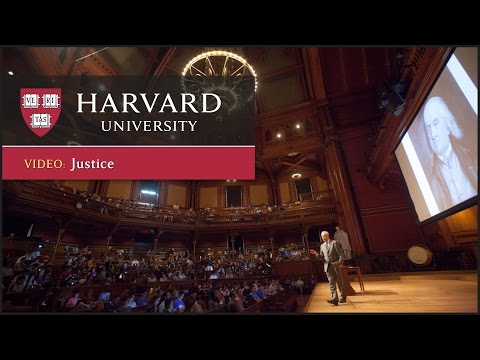

殺人の道徳 ( Justice: What's The Right Thing To Do? Episode 01 "THE MORAL SIDE OF MURDER" )

00

VoiceTube が 2013 年 03 月 04 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

wrong

US /rɔŋ, rɑŋ/

・

UK /rɒŋ/

- n.不当な行為

- adj.(道徳的に)悪い : 邪な;間違った : 誤っている;不適切な : ふさわしくない

- v.t.不当に扱う

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除