字幕と単語

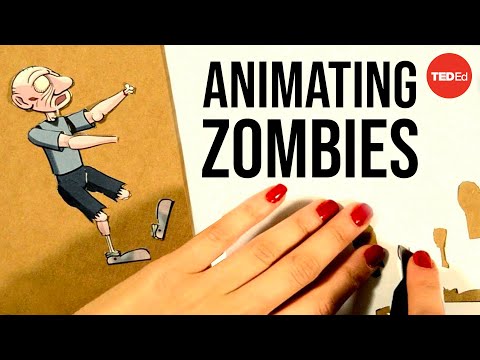

TED-Ed】TED-Edのレッスンを作る。ゾンビをアニメーション化する (【TED-Ed】Making a TED-Ed Lesson: Animating zombies)

00

陳俊安 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

draw

US /drɔ/

・

UK /drɔ:/

- v.t.引く;引き込む;引っ張る;引き出す

- n. (c./u.)引きつけるもの;くじで引き当てたもの;引き分け

- v.i.近づく;引き分けになる

- v.t./i.線を引く : 描く

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除