字幕と単語

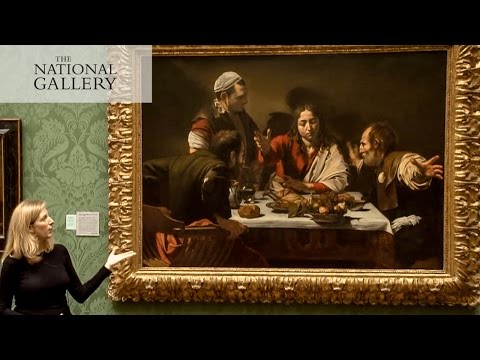

カラヴァッジョ|あなたが選ぶ|ナショナル・ギャラリー(ロンドン (Caravaggio | You choose | The National Gallery, London)

00

林容瑛 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

time

US /taɪm/

・

UK /taɪm/

- n. (u.)(音楽の)拍子 : テンポ;(時計が指し示す)時刻 : 時間;時間;(ある出来事が起きる)時 : 時点;時;時代 : 時期;時間;所要時間

- v.t.(音楽の)リズムをとる;(~するのに)ふさわしい時を選ぶ;時間を計る;(出来事の最適な時間や時期を)決める

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除