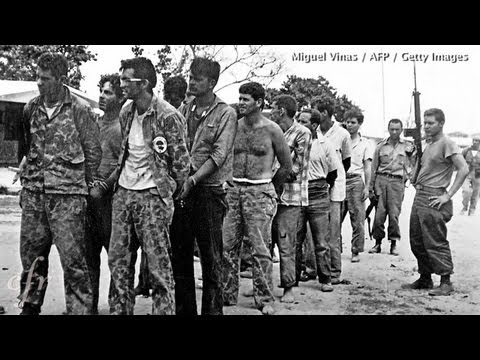

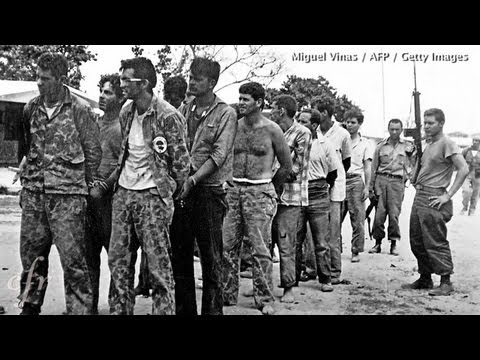

学んだ教訓豚の湾の侵略 (Lessons Learned: Bay of Pigs Invasion)

James が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /'feɪljər/

・

UK /ˈfeɪljə(r)/

- n.故障;失敗;失敗者;怠慢;崩壊;機能不全;不合格

US /ˈmɪlɪˌtɛri/

・

UK /'mɪlətrɪ/

US /ˈprɛzɪdənt,-ˌdɛnt/

・

UK /ˈprezɪdənt/

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除