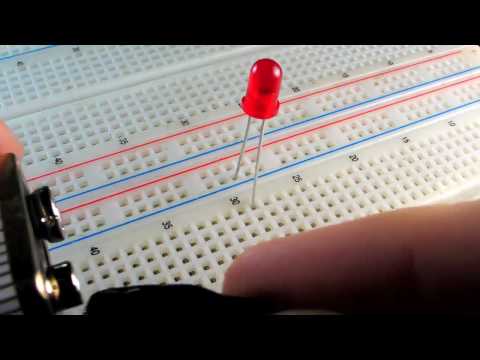

MAKEのプレゼント。LEDを使用した (MAKE presents: The LED)

Sea Monster が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /ˈnɛɡətɪv/

・

UK /'neɡətɪv/

- n.マイナスの電極;否定文の;「いや」という返事;写真や映画のネガ

- adj.嫌な;負の数の;悲観的な;否定的;陰性の;負の

US /ˈpɑzɪtɪv/

・

UK /ˈpɒzətɪv/

- adj.肯定的な;確実な;電気のプラス極;よい;陽性の;楽観的な;正の;ポジ

- n.ポジ

- n. (c./u.)(電気の)リード線;手がかり : 糸口;(映画 : 演劇の)主要部分 : 中心部;鉛;ひも : 鎖 : リード;(競争の)先頭 : 首位 : 優勢

- adj.(映画や演劇などの)主役の

- v.t.導く;(競争 : 勝負で)リードする : 先頭に立つ

- v.t./i.導く

US /ɪkˈspɛrəmənt/

・

UK /ɪk'sperɪmənt/

- n. (c./u.)実験;試み

- v.t./i.実験をする;試みる

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除