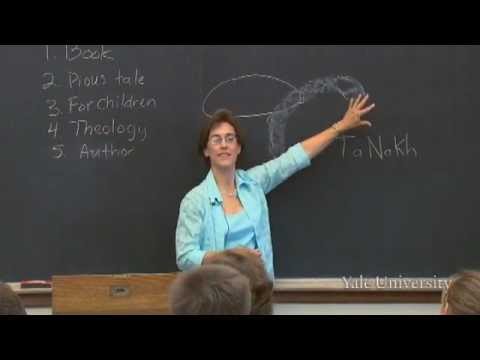

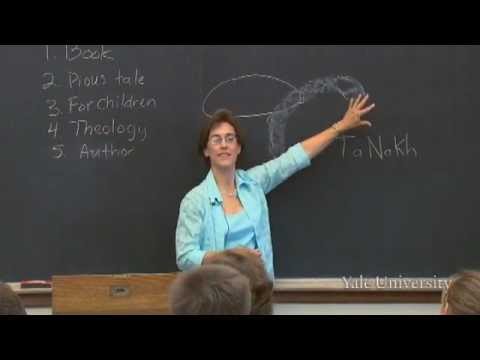

講義1.全体のパーツ (Lecture 1. The Parts of the Whole)

林雅歌 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありません- n. (c./u.)(同じ文化を共有する)民族;人々;人々;親族;社員

- v.t.居住する

- n. pl.人々

US /ˈenʃənt/

・

UK /'eɪnʃənt/

US / ˈsɛkʃən/

・

UK /'sekʃn/

- n. (c./u.)部分 : 一片;一部;章

- v.t.小さく分ける

- v.t.メールを作成

- n. (u.)文章;文章;本;テキストメッセージ;原文;歌詞

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除