字幕と単語

動画の中の単語

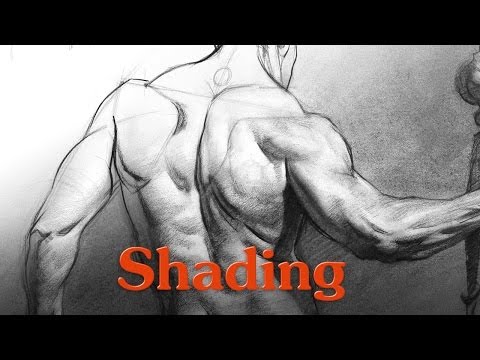

form

US /fɔrm/

・

UK /fɔ:m/

- n.スポーツのチームの試合記録;記入用紙;形 : 型 : 種類

- v.t.(集団を)結成する : 組織する;形作る : 作り上げる;形成する

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る draw

US /drɔ/

・

UK /drɔ:/

- v.t.引く;引き込む;引っ張る;引き出す

- n. (c./u.)引きつけるもの;くじで引き当てたもの;引き分け

- v.i.近づく;引き分けになる

- v.t./i.線を引く : 描く

A1 初級TOEIC

もっと見る edge

US /ɛdʒ/

・

UK /edʒ/

- n. (c./u.)人とは際立って違うもの;刃物の刃;端 : ふち

- v.t.(刃物を)鋭くする:研ぐ;縁取りをする

- v.t./i.少しずつ進む : じわじわ進む

A2 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除