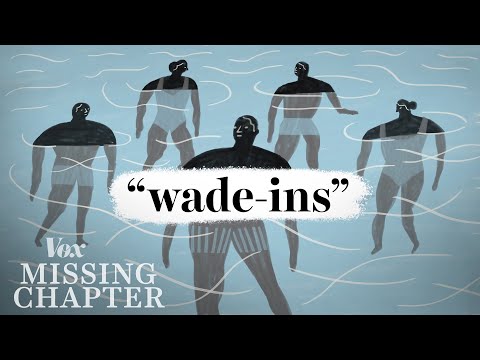

アメリカを変えた忘れられた「ウェイドイン (The forgotten “wade-ins” that transformed the US)

林宜悉 が 2020 年 10 月 08 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありません- n. (c./u.)~へ行く手段;利用する機会;アクセス

- v.t.利用可能である : 使用許可を得る

- v.t./i.アクセス;アクセスする

US /kæmˈpen/

・

UK /kæm'peɪn/

- v.i.運動を起こす

- n. (c./u.)組織的運動;作戦;選挙運動

- v.t.推進する

US /dɪˈvɛləp/

・

UK /dɪ'veləp/

- v.t./i.展開する;開発する;発達する;現像する;発症する;磨く

- v.t./i.方向を変える;移動する;シフトする

- n. (c./u.)計画や意見を変えること;(交代制の)勤務時間;勤務時間;ワンピース;地殻変動;シフトキー;変速

- adj.シフトの : 交代勤務制の

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除