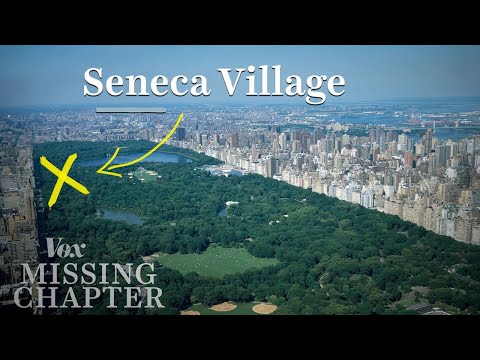

ニューヨークのセントラルパークの下の失われた地域 (The lost neighborhood under New York's Central Park)

林宜悉 が 2020 年 09 月 04 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありません- v.t.(人を騙すために)ふりをする : 装う;仮定する : 推測する;(責任 : 任務などを)負う : 引き受ける

- v.t.(報いや賞などを受けるに)値する : ~の価値がある

- n. (c./u.)(社会的)上層階級;権力を持つ人;えり抜きの人々;精鋭;エリート;(印刷)小型活字

- adj.(社会的)上層階級;権力を持つ人;精鋭な

US /kəˈmjunɪti/

・

UK /kə'mju:nətɪ/

- n. (c./u.)社会集団;一体感;オンラインコミュニティ;生物群集;実践共同体;欧州共同体

- adj.地域社会の;共同の

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除