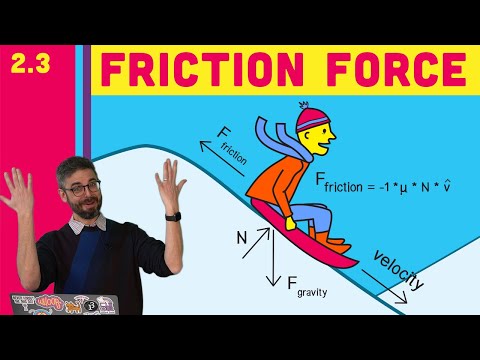

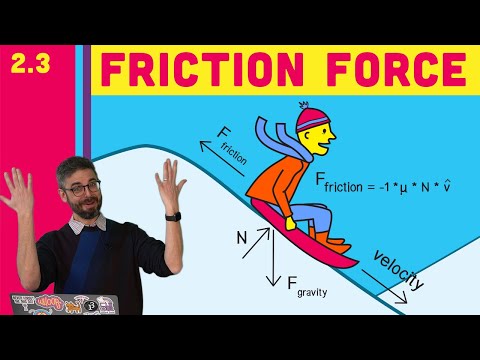

2.3 摩擦力-コードの性質 (2.3 Friction Force - The Nature of Code)

林宜悉 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /səˈner.i.oʊ/

・

UK /sɪˈnɑː.ri.əʊ/

- v.t./i.出場する;計算する;思う;思う

- n.姿 : 体形;数字;人物像;図表;著名人;姿の輪郭;数字

US /məˈtɪriəl/

・

UK /məˈtɪəriəl/

- n. (c./u.)衣料;原材料;原料

- adj.関連な,重要な;世俗的な : 物質的な : 物質でできた

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除