字幕と単語

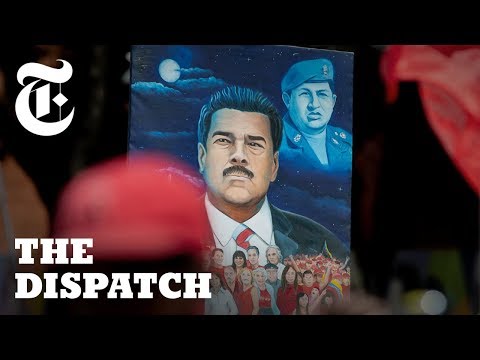

ベネズエラのブラックアウトの内部。マドゥーロの権力はどのようにして存続するのか? (Inside Venezuela’s Blackout: How Maduro’s Power Endures | The Dispatch)

00

林宜悉 が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

access

US /ˈæksɛs/

・

UK /'ækses/

- n. (c./u.)~へ行く手段;利用する機会;アクセス

- v.t.利用可能である : 使用許可を得る

- v.t./i.アクセス;アクセスする

A2 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除