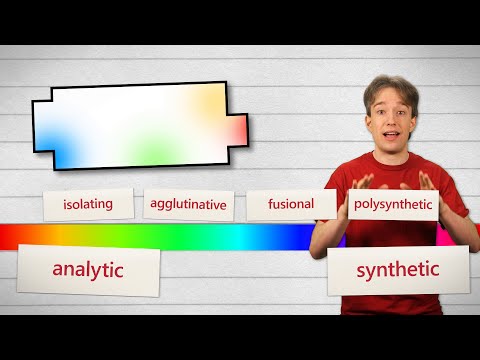

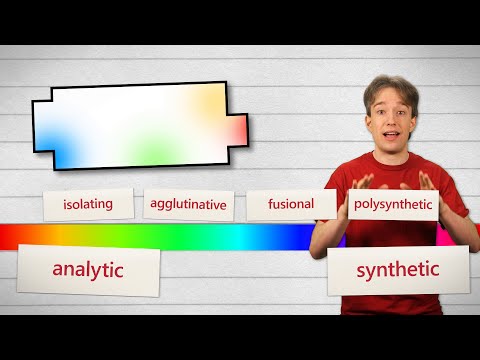

長い言葉と短い言葉。言語の類型論 (Long and Short Words: Language Typology)

Dmitry が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありませんUS /ɪnˈkrɛdəblɪ/

・

UK /ɪnˈkredəbli/

- adv.信じられないことに;信じられないほど;信じられないほど;驚くほど

US /ˈsɛntəns/

・

UK /'sentəns/

US /'sepəreɪt/

・

UK /'sepəreɪt/

- adj.違う;別々の

- v.t.離す;割く

- v.i.別居する

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除