字幕と単語

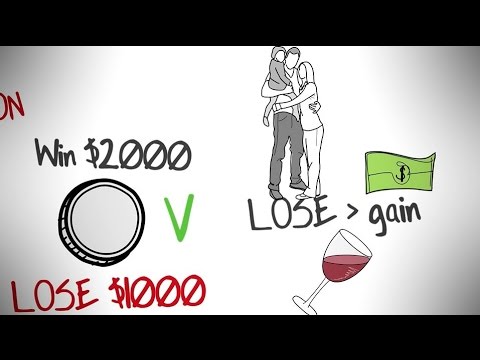

考える、速く、ゆっくり ダニエル・カーネマン|アニメ本のレビュー (THINKING, FAST AND SLOW BY DANIEL KAHNEMAN | ANIMATED BOOK REVIEW)

00

Jean Lin が 2021 年 01 月 14 日 に投稿保存

動画の中の単語

frame

US /frem/

・

UK /freɪm/

- v.t.でっちあげる;丁寧に言葉で表す;絵や写真を額に入れる;組み立てる;囲む

- n. (c./u.)額縁;骨格;骨組み;心理状態;フレーム

A2 初級TOEIC

もっと見る エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除