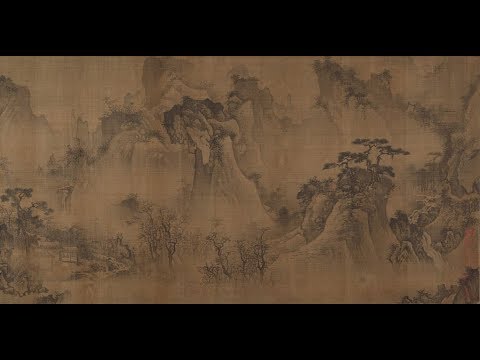

古代美術リンク - メトロポリタン美術館の中国山水画(大都会博物馆中国山水画) (Ancient Art Links - Chinese Landscape Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum (大都会博物馆中国山水画))

Ashely Ma が 2024 年 09 月 14 日 に投稿  この条件に一致する単語はありません

この条件に一致する単語はありません- n.嫌な場面、状況;風景;現場;(演劇や歌劇の)場面 : シーン

US /fɪˈlɑsəfi/

・

UK /fə'lɒsəfɪ/

US /ˈsɛntəns/

・

UK /'sentəns/

エネルギーを使用

すべての単語を解除

発音・解説・フィルター機能を解除